The Business Plan Recommendation 1

Share

[box]

Create an independent national energy strategy board.

[/box]

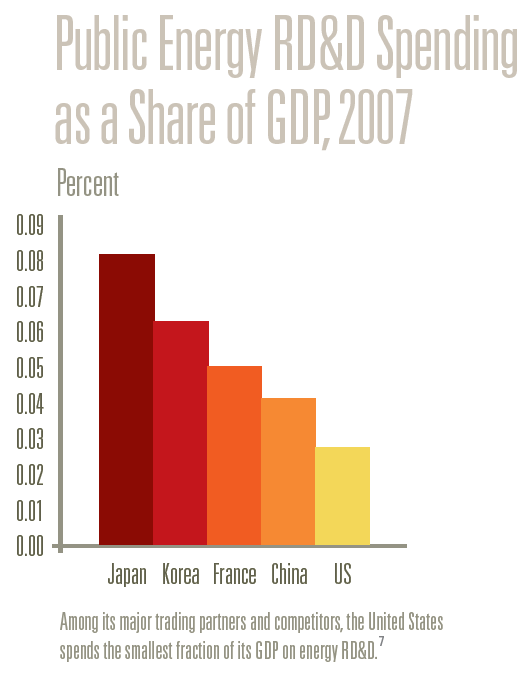

The United States does not have a realistic, technically robust, long-term energy strategy. Without such a strategy, there is no coherent way to assess energy, environmental or climate policy, nor is there a coordinated framework for developing new technologies. The result of this neglect is reflected in our nation’s history—with oil-driven recessions, trade deficits, national security problems, increasing CO2 emissions, and a deficit in energy innovation.

It is time to address our energy future with more serious purpose. To do so, we call for the creation of a congressionally mandated Energy Strategy Board. This would be a high-level board of experts charged with development and monitoring of a National Energy Plan for Congress and the executive branch, and oversight of a New Energy Challenge Program (see Recommendation 5).

National Energy Plan

The country needs a National Energy Plan. Such a plan would assess problems and opportunities, establish clear objectives, and chart a course toward achieving them. It would serve as a benchmark for national energy, climate, and environmental policy, and would guide and coordinate energy research investments by the Department of Energy, the New Energy Challenge Program5, and the Clean Energy Deployment Administration6.

The National Energy Plan should provide an ambitious but achievable strategy. The plan should contain concrete and measurable energy objectives and then allow technologies and markets to compete to meet them. For example, the United States is dependent on petroleum for 97 percent of transportation fuels. The nation would benefit from having a target to reduce that single-source dependence, and a realistic plan to get there. The National Energy Plan would map out both the policies and energy technology strategies to achieve these goals. The plan would include metrics against which progress can be measured.

The National Energy Plan should provide an ambitious but achievable strategy. The plan should contain concrete and measurable energy objectives and then allow technologies and markets to compete to meet them. For example, the United States is dependent on petroleum for 97 percent of transportation fuels. The nation would benefit from having a target to reduce that single-source dependence, and a realistic plan to get there. The National Energy Plan would map out both the policies and energy technology strategies to achieve these goals. The plan would include metrics against which progress can be measured.

The plan would also assess political path dependence questions that require resolution if the United States is serious about taking on our energy challenge. The government’s decisions on these fundamental issues should drive America’s energy technology strategy.

For example:

- Is the federal government willing to take on long-term liability for storing CO2 through carbon capture and storage (CCS)? Or for storing nuclear waste?

- Can the utility industries be reformed to align with the nation’s 21st century aspirations of deploying innovative energy technologies and creating a robust, modern grid?

A National Energy Plan cannot just be the sum of the advocacy of different energy interests. It needs to be built upon an in-depth assessment of end uses (transportation, housing, industry, etc.) and their potential for improvement; a complementary assessment of energy supply options (electric, liquid, and gaseous fuel sources as well as the technologies used in power generation); and a plan for the infrastructure that conveys that energy (storage, transmission, and distribution). For each realm, the analysts must understand technical potential, cost curves, research frontiers, economics, scaling potential, and siting characteristics. They will also need a keen sense of the effects and side effects of various energy policies. All of that option-specific work will then need optimization.

Many technologies depend on each other. For example, massive renewables deployment will require some combination of enhanced electric transmission capacity, storage, back-up capacity, and demand control. It makes little sense to push renewables without developing an intelligent combination of these four complementary technologies.

Today, these technologies are developed largely in isolation from each other. Naturally, the plan must take advantage of the dynamics of the private sector, which is the best engine for innovation and for allocation of capital. This report makes clear that we believe the federal government has a crucial role—in setting energy policy, undertaking research and development, and demonstrating large-scale technologies. But that work, and the National Energy Plan, will all fail if the government does not help unleash large private sector commitments and innovation. The National Energy Plan must be cognizant of the conditions that accelerate private investment.

The Energy Strategy Board would be responsible for generating the Plan and updating it every three years. It would produce a formal report to the federal government, and would require the U.S. secretary of energy and other relevant agency administrators to respond.

The Energy Strategy Board would also charge the Energy Information Administration (EIA) with scoring how energy policy affects the nation’s energy future. Today, the Office of Management and Budget and the Congressional Budget Office track the fiscal impacts of various policies with an overall budgetary strategy in mind. The EIA currently has no overall strategy against which to track the energy impacts of energy bills. This needs repair, and the Energy Strategy Board would be ideally positioned for the job.

New Energy Challenge Program

This report argues for a special federally chartered corporation to develop and demonstrate large-scale energy technologies, such as advanced nuclear power, or carbon capture and storage for coal. Without such an institution, these options will stagnate—as they have in the United States—for decades.

The New Energy Challenge Program (NECP) is described in more detail as Recommendation 5. We envision an independent institution tasked with demonstrating advanced energy technologies at commercial scale. The NECP would be a subsidiary organization of the Energy Strategy Board, with its own small executive management authority. The NECP would be organized around the Board’s stated technology priorities.

Staffing and funding

The Energy Strategy Board would be a small, politically neutral, high-level group, with a lean operating budget and a focused mandate. It would have one federally-appointed chair and about 15 members made up of preeminent figures in the energy domain, such as leaders of the National Academies and relevant company executives. The members of the Board would be selected by their peers, rather than the political process.

Slots on the board should be reserved for the sitting directors of ARPA-E and the Clean Energy Deployment Administration, as well as the President of the New Energy Challenge Program (see Recommendation 5). Other positions would be filled with experts on technology development, such as Chief Technology Officers and experts in energy policy. The Energy Strategy Board would require a small, highly competent staff for production of the National Energy Plan, and it would have broad authority over the budget of the New Energy Challenge Program.