Catalyzing Ingenuity Chapter 1

Share

[box]

Why does government need to play a role in supporting energy innovation?3>[/box]

The Importance of Innovation

Technology innovation has long been central to American prosperity and to American leadership on the world stage. From its beginnings, the United States fostered a market system that allowed for the free flow of ideas, capital, and people. Over time, this system has proved uniquely successful in unleashing the creativity and entrepreneurial ambitions of individual citizens and in harnessing those energies for productive and wealth-generating purposes. As Joseph Stiglitz said in his acceptance speech for the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics: “Changes in technology, R&D, are at the heart of capitalism.”1 From gas turbines to smartphones, medical imaging to communications satellites, GPS to the internet, innovation has improved lives, created jobs, and supported more than a century of U.S. preeminence economically, technologically, and militarily. As business leaders we are acutely aware that America’s future success depends on its ability to carry forward this tradition of innovation and continue generating new ideas, technologies, processes and products.

Of all the sectors in the economy where innovation has a critical role to play, the energy sector stands out. Ready access to reliable, affordable forms of energy is not only vital for the functioning of the larger economy, it is vital to people’s everyday lives and significantly impacts the country’s national security and environmental well-being. Innovation-driven improvements in energy productivity in the late 19th century (especially the development of the electricity, automobile, and oil industries) gave consumers unprecedented improvements in quality of life. Although these innovations drove economic growth for much of the 20th century, they also prompted rapid growth in domestic and global energy demand.

At this point in history, securing clean, scalable and inexpensive energy supplies is a high-stakes innovation challenge. Failure would almost certainly lead to a lower quality of life for most Americans, but success will open up vast new markets and establish U.S. leadership while making our world cleaner and more secure.

But all this is well known. We all agree that technology innovation has boosted our economy and improved lives. We all agree that to break out of our current economic malaise, America needs to innovate, manufacture and build new technologies. This is true in many sectors of our economy, and it is certainly true in energy.

Where the consensus breaks down, however, is in deciding how the country should set out to achieve a leadership position in future energy markets. In these debates, some argue that government serves little essential role in innovation (other than enforcing the rule of law and preserving the sanctity of contracts) and that actual innovation - especially for energy - should be solely in the hands of the private sector.

Where the consensus breaks down, however, is in deciding how the country should set out to achieve a leadership position in future energy markets. In these debates, some argue that government serves little essential role in innovation (other than enforcing the rule of law and preserving the sanctity of contracts) and that actual innovation - especially for energy - should be solely in the hands of the private sector.

Based on history and on our own experiences leading innovative companies, we disagree. Although we agree that the private sector is and will continue to be an important source of innovation, we believe the federal government has an integral role to play in advancing energy innovation - specifically in energy research, development and demonstration (RD&D).

The Case for an Active Government Role in Energy Innovation

The U.S. innovation engine is the envy of the world. In fact, throughout the nation’s history, businesses, entrepreneurs, and researchers have worked to create new, game-changing technologies in a host of sectors. In the process, they have profoundly changed the status quo. While businesses have driven much of this progress, targeted and deliberate public support has also been crucial. At the most basic level, government’s role in innovation is to foster an environment that is conducive to the creation, development, and commercialization of new ideas and technological advances. This notion is widely accepted and dates back to the founding of the republic; indeed, the U.S. Constitution recognized the awarding of patents “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” as one of the central functions of a national government.2 But the role of government goes beyond creating the right market and institutional environment. In fact, the U.S. government has a long and successful history of supporting publicly-funded research and development (R&D) as well as demonstration projects, procurement practices, and other policies (taxes, subsidies, regulations, etc.) that foster the development of new technologies.3

The rationale for government intervention is two-fold. First, history shows that support for innovations that serve a fundamental national interest cannot be left to the private sector alone. Private markets generally do not exist for certain benefits, such as providing for a strong military, improving public health, and protecting the environment. Therefore, it falls to government to ensure that these benefits are supplied at the level society demands. A second rationale rests on the theory and practice of knowledge spillover and the ‘free-rider’ problem. When firms make investments in basic science or R&D, they create knowledge spillovers that benefit society as a whole, as well as other firms. Those other firms get a free ride on their competitors’ R&D investment. Because it is difficult for any individual firm to monetize all the benefits of these types of investments, the private sector has tended to systematically under-invest in R&D relative to the potential gains to society - even where a market for the desired technology exists.

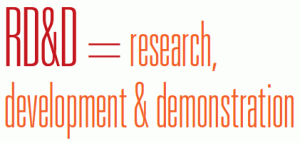

In fact, real-world evidence supports the proposition that important energy industries are even more likely to under-invest in R&D than other sectors. Utilities, in particular, steer remarkably few resources to R&D. Across all U.S. industries, private firms spend an average of 3.5 percent of revenues on R&D.4 By contrast, utility spending on R&D averages 0.1 percent of revenues. Moreover, Figure 2 shows that utility R&D spending has declined in absolute terms since the mid-1990s.5 Although on average U.S. firms employ 63 R&D engineers and scientists per 1,000 employees, utilities employ just 5 - fewer than any other sector and trailing far behind the next-lowest sector, which is retailing (with 9 R&D personnel per 1,000 employees).6 As executives, we know that these current resource commitments are not sufficient to support a fundamental transformation of today’s energy systems.

Under-investment in R&D is, not surprisingly, much less of an issue where strong market incentives exist for technology improvement. It is not clear, for example, that government support is needed to advance oil and gas exploration and drilling technologies. On the other hand, where public interests that are not valued in the marketplace are at stake, government may be the only or primary driver of innovation. In the case of climate change, the current absence of comprehensive regulation of greenhouse gas emissions means that private firms face weak or non-existent incentives to pursue low-carbon innovations. The challenge this creates is compounded by other features, unique to the energy sector, that present additional hurdles to innovation.

One is that energy is generally not valued for its own characteristics, but rather for the goods and services it enables. As a commodity, one kilowatt-hour of electricity is indistinguishable from any other kilowatt-hour - regardless of how it was generated. Similarly, most people don’t care what they put in the gas tank, provided their vehicle can travel equally far for the same money. This means that product differentiation does not drive innovation in energy supply options in the same way that it would for other types of products and services.7

A second impediment to innovation in the energy realm is that many of the technologies and systems involved are capital intensive and long-lived. This is true on both the supply side of the equation (e.g., power plants, pipelines, and refineries) and on the demand side (e.g. buildings and automobiles).8 Slow turnover of capital assets combined with the fact that many new energy supply or end-use technologies require large up-front investments mean that the sector as a whole is subject to a high degree of inertia, a tendency to avoid risk, and domination by incumbent firms. Markets do not drive innovation especially well for investments that are lumpy, high-cost and high-risk-particularly when the outcomes of these investments play out over decades in a context where energy prices are volatile and many facets of our national energy policy are in flux. The magnitude of required investments to develop new energy technologies is markedly different from many other technologies. It is one thing to prototype a new smartphone; it is quite another to prototype a new nuclear reactor.

A second impediment to innovation in the energy realm is that many of the technologies and systems involved are capital intensive and long-lived. This is true on both the supply side of the equation (e.g., power plants, pipelines, and refineries) and on the demand side (e.g. buildings and automobiles).8 Slow turnover of capital assets combined with the fact that many new energy supply or end-use technologies require large up-front investments mean that the sector as a whole is subject to a high degree of inertia, a tendency to avoid risk, and domination by incumbent firms. Markets do not drive innovation especially well for investments that are lumpy, high-cost and high-risk-particularly when the outcomes of these investments play out over decades in a context where energy prices are volatile and many facets of our national energy policy are in flux. The magnitude of required investments to develop new energy technologies is markedly different from many other technologies. It is one thing to prototype a new smartphone; it is quite another to prototype a new nuclear reactor.

A third issue is that energy markets-particularly for electricity - are far from perfectly competitive. The power sector, which is heavily regulated at the state level, is especially fragmented, but energy markets more generally may be slow to adopt innovations because of regulatory uncertainty, lack of information, and distortions introduced by past policies-including numerous existing subsidy programs.

All of these factors together create a clear and compelling justification for direct government support of energy innovation, particularly given the economic, national security, and environmental interests at stake. The question is not so much whether active intervention can be justified, but rather the details around how that intervention should happen and to what extent.

The U.S. Government’s History of Support for Technology Innovation

The federal government has played a central role in catalyzing and driving innovation and technology development throughout the history of the United States - often with strong results. This kind of support took a variety of forms. In the 19th century, government scientists mapped out natural resource endowments and Army officers surveyed routes for railroads, including helping to plan and sometimes to manage their construction. In the early and mid-20th century, programs such as rural electrification and massive public works projects, such as the construction of the Interstate Highway System, enhanced mobility and connectivity and directly or indirectly contributed to the development of new technologies and industries.

Modern arguments for a sustained, broad-based government role in basic science and technology R&D did not emerge, however, until World War II revealed that America was lagging far behind Britain and Germany in the development of critical military technology such as radar and jet engines.9 Since then, the U.S. government has supported a vast array of technologies and scientific enterprises with considerable success. For instance, government efforts to develop guidance systems for the military played a role in the development of digital computers and microchips. Navy support for aviation technology led directly to Boeing’s 707 - one of the first major commercial jetliners. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) created a distributed network of computers called ARPANET, which laid the early foundation for the internet. The U.S. government played a direct and indispensable role in launching the commercial nuclear power industry. Much of the initial technological know-how was developed through government efforts - working with firms like GE - to design nuclear power reactors for the Navy, and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) then extended financing to utilities for a series of demonstration plants. Global Positioning System (GPS) technology was invented by the military but was opened to widespread commercial use in 1996 and is now omnipresent in communications and transportation systems. In fact, government support for basic research and for the mission-driven programs of agencies like the Department of Defense (DOD) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has sparked a long list of landmark innovations.10

In many of these cases, government innovation efforts involved the private sector, which often conducted design, development, demonstration, and testing of systems and equipment under contract to federal agencies. Those systems and equipment often had important spin-offs; in particular, jet engines and gas turbines both found important applications in the energy sector, multiple sectors of the economy make use of Earth-orbiting satellites and remote sensing, and a host of less visible technology advances such as fiber-reinforced composite materials and micro antennas have been incorporated into numerous consumer products. These innovations enabled the United States to lead not just in specific technologies but in entire industries. Federal efforts thus far in support of clean energy R&D have been inadequate to the task and paltry in comparison with other sectors.11

Energy Innovation Should be a Higher National Priority

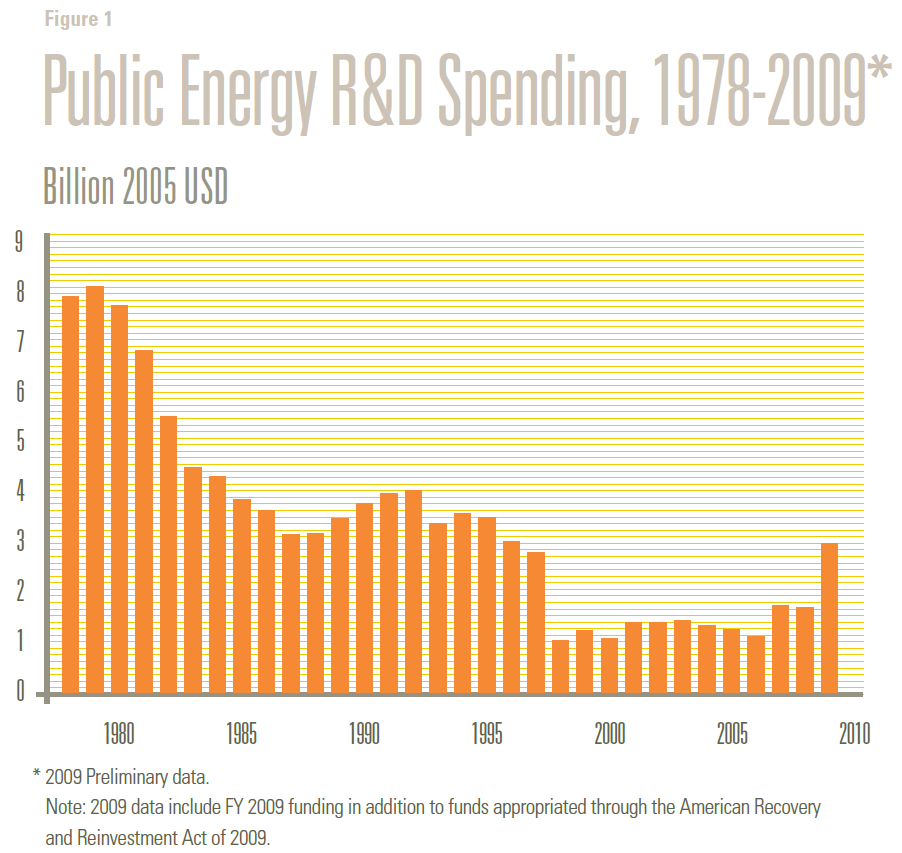

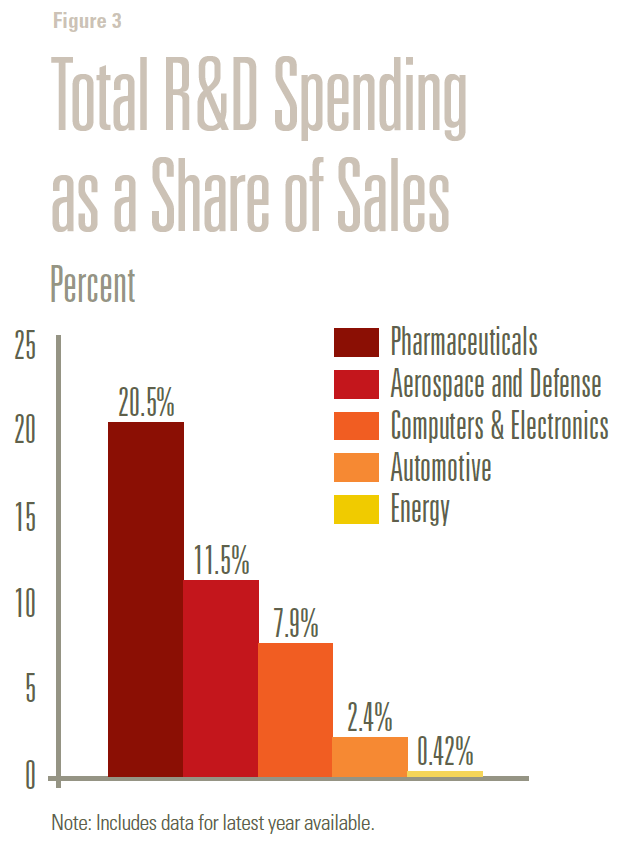

Today, federal funding for all types of R&D totals nearly $150 billion per year. This funding flows through 30 different agencies in the executive branch: half (along with 70 R&D-supporting sub-agencies) are in federal agency departments (this former group includes DOD and DOE), and half are “independent” and outside of direct presidential control (this latter group includes the National Science Foundation and NASA). Many of these federal agencies in turn fund research by private firms, universities, nonprofits, and the government’s own laboratories. Each of these agencies manages its research programs differently. This decentralization has had certain advantages, but has also led to inconsistency, duplication, and gaps in the national R&D portfolio. Support for energy R&D constitutes a relatively small part of the overall federal R&D portfolio - representing less than 2 percent of the total federal R&D budget.

We believe this must change. Energy innovation should be a higher national priority.

It is increasingly clear that the nation simply cannot afford to leave future energy technology challenges solely to the marketplace. The environmental and economic trade-offs in energy, domestically and globally, are becoming more urgent and more complex. At the same time, jobs and international competitiveness considerations have moved to the forefront of the nation’s priorities. The governments of China, Germany, Japan, and Korea, among others, are all making significant investments in energy innovation. This is creating large new markets and millions of high-paying jobs in manufacturing and services, and will undoubtedly shape the future evolution of the $5 trillion global energy industry.

We strongly recommend increased government support and leadership to develop and demonstrate new energy technologies to meet this century’s challenges. The more difficult question is how to ensure that government plays this role more effectively.